The Armorican Merlin

Merlin in Breton Literature and Folklore

This website is dedicated to Breton material concerned with the character of Merlin and its various avatars. The aim of this project is to raise awareness as to the Armorican material surrounding the character, which is often unknown to English-speakers, even within the field of Celtic Studies.While information is given about each item, the main focus is to give access to the primary sources themselves rather than comment upon them.Arthurian material from Brittany in which Merlin is not present (such as the Life of Saint Ke or the Life of Saint Efflam) are not listed on this website. Neither are 19th and 20th c. reimaginings and literary works, such as Xavier de Langlais's Marzhin (1975).

If you are interested in the Welsh Myrddin tradition and poetry, more is available at https://myrddin.cymru/.

Résumé en français

Ce site internet a pour but de cataloguer et présenter les sources primaires concernant Merlin en Bretagne armoricaine. Le matériau arthurien dans lequel Merlin ou ses avatars n'apparaissent pas n'est pas listé ici.Ce site n'est pour l'instant disponible qu'en anglais. La plupart des sources et travaux concernant le Merlin armoricain sont disponibles en breton ou en français, rendant le matériau plus accessible aux bretonnants et francophones. Vous pouvez consulter la page Bibliography pour trouver une liste d'articles, études, et éditions de sources présentées ici.Qui plus est, certaines pages contiennent les transcriptions des originaux bretons ou français, que vous pouvez ainsi consulter directement.

Un certain nombre de textes liés au Merlin gallois (Myrddin) sont disponibles sur le site https://myrddin.cymru/ (gallois/anglais).

Corpus

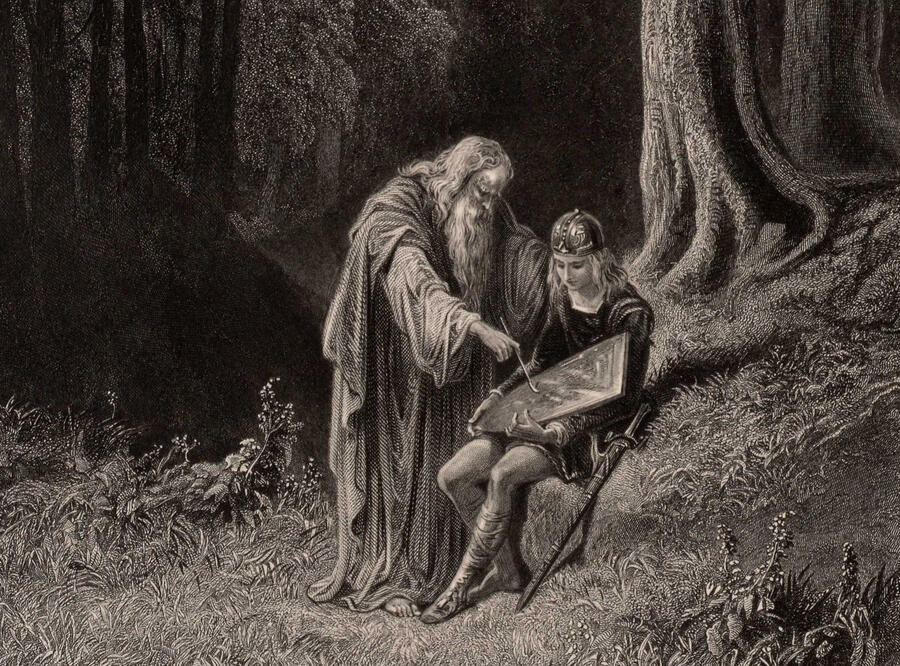

Gustave Doré, Merlin découvert par le Roi Arthur, 1868.

Below are links to all the catalogued sources from Brittany about Merlin and his avatars. They have been divided in categories (Literary Sources, The Tale of Merlin, Folk Sources about Gwenc'hlan, and Other Folk Sources) for ease of navigation. Some entries contain transcriptions and translations of texts whenever length allows. References are all in the bibliography of this website.

Literary Sources

The Tale of Merlin

The Popular Sources on Gwenc'hlan

Other Folk Sources

An Dialog etre Arzur Roe dan Bretounet ha Guynglaff

The dialogue between Arthur, King of the Bretons, and Guynglaff

Type: Prophetic text, versified

Language: Middle Breton

Date: 15th or 16th c.

Manuscript: Bibliothèque Rennes Métropole (BRM) Ms 1007, pp. 1426-1441.

English Edition: Minard, Antone. 1999. “‘The dialogue between King Arthur and Gwenc'hlan’: a translation” in Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Vol. 30, pp. 167–179.

French Edition: Bihan, Hervé. 2013. An Dialog etre Arzur Roe dan Bretounet ha Guynglaff (Rennes: TIR).

This text has long been considered the only example of medieval, Arthurian literature in the Breton-language, with a traditional date of composition 1450 (Bihan, 2013). However, a recent study by Shales (2025) challenged that date pushing it back to the late 16th century. Shales also argues against the view that the text is the result of several copies and rewritings from an older original, arguing that it was composed by one single author and has reached us almost intact.

Regarless of the date of composition, the text calls upon broader Breton-themes surrounding Merlin: Guynglaff is a prophetic figure living in the woods, and is captured by King Arthur to speak prophecies about the future of Brittany.

The character of Guynglaff (MBr Gwenc’hlan, also attested as Gwiklan or Guiclan) appears elsewhere in Breton folklore (see dedicated pages on this website). Bihan provides a full pedigree of the character, an indepth discussion of his ties to popular tradition (2013), as well as a demonstration of his nature as an avatar of Merlin.

Opening lines (Le Bihan’s reading) & translation (FBG)

Dre gracz Doe ez veve,

N’en devoe ez dre voe en beth

Nemet en delyou glas,

N’endevoe quen goasquet,

An re-se en beve,

N’endevoe quen boet.

Didan un casul guel ez voe,

Nos ha dez en e buhez en beth,

Digant Doe endevoe e gloar en eff,

Ha ne manque quet.

Dre Graçç Doe ez gouuie,

Doediguez flam an amser divin illuminet

An Roe Arzur en ampoignas da Sul,

Pan savas an heaul un mintin mat,

Ha dre cautel ha soutildet

Ez tizas e dorn, ha e quemeret.

Maz goulennas outaff hep si

En hanu Doe, me oz supply,

Dan Roe Arzur ez liviry

Pebez sinou e Breiz a coezo glan,

Quent finuez an bet man,

Na pebez feiz, lavar aman :

Pe me az laquay e drouc saouzan.

By the grace of God he lived,

He had while he was in this world

Only the green leaves,

He only had their shelter,

They would feed him

He had no other food.

He went under a brown cape,

Night and day in his life in this world,

He had glory in the heavens from God,

And he lacked nothing.

By the grace of God he knew,

The true coming of the divine, enlightened time

King Arthur caught him one Sunday,

When the sun rose in the early morning,

And through trickery and subtlety

He reached his hand, and took him.

Then he asked of him without hesitation

In the name of God, I beseech you,

You will tell to King Arthur

Which signs will come to Brittany surely

Before the end of this world

And which faith, tell me here:

Or I will put you in an ill situation.

Further reading

• Bihan, Hervé. 2013. An Dialog etre Arzur Roe dan Bretounet ha Guynclaff (Rennes: TIR).

• Bihan, Hervé. 2009. “An Dialog etre Arzur Roe d'an Bretounet ha Guynglaff and its Connections with Arthurian Tradition” in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, Vol. 29, pp. 115-126.

• Constantine, Mary-Ann. 1995. “Prophecy and pastiche in the Breton ballads: Groac'h Ahès and Gwenc'hlan” in Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, Vol. 30, pp. 87–121.

• Ernault, Émile. 1930. “Sur le prophète Guinclaff” in Annales de Bretagne, 39/ 1, pp. 18-30.

• Minard, Antone. 1999. “‘The dialogue between King Arthur and Gwenc'hlan’: a translation” in Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Vol. 30, pp. 167–179.

• Piriou, Jean-Pierre. 1985. “Un texte arthurien en moyen-breton : le dialogue entre Arthur roi des Bretons et Guynglaff” in Actes du 14ème congrès international arthurien, Tome 2 (Rennes: PUR), p. 474-499.

• Shales, Jess. 2025. “On the date of the Dialog: A re-examination of the date of composition of the earliest Arthurian poem in Middle Breton,” in Celtica, Vol. XXXVI (Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies), pp. 193-223.

Chronicles

Type: Historical chronicles

Languages: Latin & French

Date: 14th, 15th, & 16th c.

Breton medieval chronicles reference Arthurian material as historical sources, with a particular reliance on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work. The three chronicles which are of importance for Merlin in Brittany are the Chronicles of Saint Brieuc (Chronicon Briocense, late 14th c.), the Compillation des cronicques et ystoires des Bretons (1480) by Pierre Le Baud, and the Grandes Chroniques de Bretagne (1514) by Alain Bouchart.The first, while oftentimes copying or adapting Monmouth, includes long reflections by the chronicler on the Prophecies of Merlin and their ties to Breton and broader Brittonic history (in particular chapters 35-45). It also includes details, anecdotes, and additions which are not from Monmouth, and the author had access to Arthurian material from Brittany that is now mostly lost, like the Vita Goeznovii (11th c.). A complete edition of the Chronicles was unfortunately never completed, but an important part of the Arthurian material, as well as these analysis of the prophecies by the anonymous chronicler, are in Le Duc and Stercx’s 1972 edition (see reference below).Pierre Le Baud’s own history of Brittany makes use of the Chronicon Briocense as well as another text, now mostly lost to us, which he calls the Livres des Faits d’Arthur le Grand (Book of the Deeds of Arthur the Great). What remains of that book is a Latin poem (Archives Départementales d’Ille-et-Vilaine, MS 1 F 1003, ff. 187-195) about Magnus Maximus and Conan Meriadec. Bourgès (2007) demonstrated that these known passages are quoted often verbatum by Le Baud, suggesting that other quotations by him are faithful to the now lost original. Le Baud also had access to some of the Chronicon Briocense's Arthurian sources such as the Vita Goeznovii.As for Alain Bouchart, he was tasked to write his chronicles after Le Baud was considered too legendary, in order to provide what was considered a more historically anchored work. As expected, Merlin appears within the covering of the pre-Arthurian and Arthurian eras.To these three texts can be added the Gesta Regum Britanniae, a 13th c. versified version of Monmouth Historia Regum Britanniae thought to have been composed in Brittany. Like in the Historia, Merlin appears in the Gesta. Further work on the Breton text is needed, and may reveal interesting additions or choices by the author, thought to be the monk William of Rennes.Finally, it is worth noting that Arthurian onomastic, including names of Merlin, is present in the Cartulaire de Redon on several occasions (see in particular Bihan, 2019).

Further reading

• Baud (Le), Pierre (author), and Karine Abélard (ed.). 2018. Compillation des cronicques et ystoires des Bretons, Sources médiévales de l'histoire de Bretagne, n° 8 (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes/SHAB).

• Bihan (Le), Hervé. 2019. "Arthur in Earlier Breton Traditions, in Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan, and Erich Poppe, Arthur in the Celtic Languages: The Arthurian Legend in Celtic Literatures and Traditions* (Cardiff: University of Wales Press), pp. 281-303.

• Bourgès, André-Yves. 2007. “La cour ducale de Bretagne et la légende arthurienne au bas Moyen Âge: Prolégomènes à une édition critique des fragments du Livre des faits d'Arthur” in Britannia monastica, Vol. 12, p. 79-119.

• Duc (Le), Gwennaël, and Claude Stercx (ed.). 1972. Chronicon Briocense. Chronique de Saint-Brieuc, fin du XIVe siècle, éditée et traduite d'après les manuscrits BN 6003-BN 8899 (Archives départementales d'Ille-et-Vilaine 1 F 1003) (ch. I à CIX) (Rennes: Simon).

• Michel, Francisque. 1862. Gesta Regum Britanniae. A Metrical History of the Britons (Cambrian Archaeological Association). Online.

Vita Sancti Judicaelis

The Life of Saint Juidcaël

Type: Saint Life

Language: Latin

Date: 11th or 12th c.

Manuscripts: BNF Latin 6003, ff. 51-59 & BNF Latin 9888, ff. 48-56.

French Edition: Fawtier, Robert. 1925. “Ingomar, historien breton” in Mélanges d'histoire offerts à Ferdinand Lot (Paris: Edouard Champion).

Taliesin mostly appears as a bard and as the reincarnation of Gwion Bach in Welsh medieval literature. In Brittany, he only appears in one text, the Vita Judicaelis (Life of Saint Judicael), dated by some to the early 11th century (Fleuriot, 1981), and by others to the 12th century (Bourgès, 2004), though the manuscripts themselves are later, being of the Chronicles of Saint-Brieuc (BNF Latin 6003, ff. 51-59, & Latin 9888, ff. 48-56). In this passage, which appears at the beginning of the Vita, King Judael of Domnonea has a dream that he cannot make sense of. He sends for Taliesin the Bard, who interprets it as a sign of the birth of Judicael, who will become both a great king and a holy man.Taliesin has been associated to the Welsh Myrddin, and he certainly presents in the Breton text various traits that link him to the Armorican Merlin: He lives outwith society (in a monastery), he is consulted by the king who needs to go find him in the liminal space he lives in, and he is gifted with prophetic powers. The episode is discussed by Fleuriot (1981) and Koch (2002).A similar episode appears in the Life of Saint Onenne, Judicael’s sister, collected from oral tradition in the 18th century (Piéderrière, 1860). In it, young Onenne is brought to an otherwise unknown saint called Elocan, who lives in the wood. The hermit predicts the princess’s transformation into a saint. This results in Onenne’s rebirth in Christ, leading her to a life dedicated to her faith. Elocan may be a Christianised Merlin figure, and his name related to Lalocan, the Armorican form of Lailoken (Bihan-Gallic, upcoming).

Original text (Fawtier's reading)

Et ipse i Judaelus evigilans e sompno et mane consurgens cepit intra se memorari et mirari visionis sue. Et protinus misit aliquem sibi fidelem ad provinciam Gueroti, ad locum Gilde, ubi erat, religionem suam peregrinus et exul transmarinus colens, Taliosinus bardus filius donis fatidicus presagissimus per divinationem prefugorum qui preconio mirabili fortunatas vitas et infortunatas disserebat fortunatorum virorum et infortunatorum per fatidica verba. Et consuluit eum nuncius per hanc simplicem nunciationem quasi Judaelus presens dicens : « Conjector optime conjectorum vidi sompnium mirabile quod narrans multis a nemine audivi interpretationem ejus ». Et per totum ut ante retuli enarravit nuncius Taliosinum sompnium domini sui Judhaeli de poste et ornamentis ejus. Et tunc Taliosinus e contra respondens dixit : « Sompnium quod audio mirabile est et rem mirabilem significat ac denunciat. Hoc est dominus tuus Judaelus bonus et felix in regno suo sedet et regnat et ex filia Ausochi quam antea commemorasti filium meliorem et multo feliciorem in regno terrestri et celesti habcbit de quo Deo donante oriundi sunt filii fortissimi totius nationis Britonum ex quibus orientur comites regales et sacerdotes celicole quibus obedient et servient vernaculi patrum suorum per totam regionem a minimo usque ad maximum. Et filius prothogenus de quo ortus est sermo multum prevalebit in militiam terrenam et exinde in militiam celicolam. Initium enim seculare et consummationem deicolam habebit. Laicus militavit seculo clericus serviet Deo ». Et sicut hec fatidica verba locutus est Taliosinus ex conjectura sua et a famulo suo nunciata sunt Judaelo comiti ita postea probavit eventus.

Translation (Google translate with corrections by FBG)

[King Judael had a strange dream.] And Judael himself, waking up from sleep and rising in the morning, began to remember and to wonder about his vision. And immediately he sent someone faithful to him to the province of Gueroti, to the place of Gildas, where there was a pilgrim in religious exile abroad: Taliesin the Bard, son of Donn, was a most insightful prophet and master of divination, who prophesised both the fortunes and afflictions of fortunate and unfortunate men by his words. And the messenger consulted him about this prophecy, as if Judael himself were present, saying: “O best prophet among prophets, I have seen a wonderful dream, which I have related to many, but none could interpret it.” And the messenger related to Taliesin the dream of his master Judael about the post and its ornaments, as I have related before. And then Taliesin, answering in return, said: “The dream which I hear is wonderful and signifies and announces a wonderful event. It is your lord Judael, good and happy, who sits and reigns in his kingdom, and from the daughter of Ausochus whom you mentioned before, he has a better and much happier son in the earthly and heavenly kingdom, from whom, by God’s grace, the bravest sons of the entire nation of the Britons will be born, from whom will arise royal earls and heavenly priests, whom the natives of their fathers throughout the whole region will obey and serve. And the firstborn son of whom the word has arisen will greatly prevail in the earthly host and from there in the heavenly host. For he will have a secular beginning and a divine end. A layman he will fight in the world, a cleric he will serve God.” And just as Taliesin spoke these fateful words from his prophecy, so they were reported by his servant to Lord Judael, and later events proved them true.

Further reading

• Fleuriot, Léon. 1981. “Sur quatre textes bretons en latin : le «Liber vetustissimus» de Geoffroy de Monmouth et le séjour de Taliesin en Bretagne,” in Etudes Celtiques, Vol. 18, pp. 197-213.

• Koch, John T. 2002. “De Sancto Iudicaelo rege historia and its implications for the Welsh Taliesin” in Nagy & Jones, Heroic Poets and Poetic Heroes in Celtic Traditions (Dublin: Four Courts Press), pp. 247-62.

Buez Santez Nonn ha Sant Dewi

The Life of Saint Nonn and Saint Dewi

Type: Mystery Play

Language: Middle Breton

Date: 15th c.

Manuscript: BNF, MS celtique 5, Buez Santez Nonn ha Sant Dewi. Available online on Codecs Vanhamel, f. 15.

French Editions: Ernault, Emile (ed). 1887. "Vie de Sainte Nonn" in Revue Celtique, Vol. VIII, pp. 230-301 & 406-491.

Le Berre, Yves, Bernard Tanguy, and Yves-Pascal Castel. 1999. Buez Santez Nonn, Mystère Breton, Vie de sainte Nonne (Rennes: C.R.B.C. & Minihi-Levenez).

The Life of Saint Nonne is a 15th century, Middle-Breton mystery play telling the life of the eponymous saint and of her son, Saint Dewi. The text calls upon several characters of Brittany’s early history, such as Saint Gildas and Saint Patrick. Before the birth of Dewi, Merlin (here named Ambrosius Merlinus) appears to prophecise the birth of the child. He no longer appears in the play after that.

Original text and translation

Ambrosius Merlinus

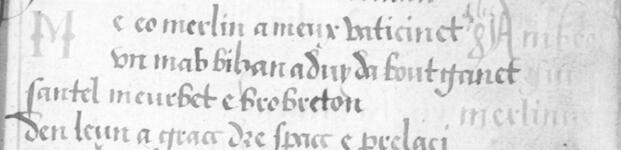

Me eo merlin a meux vaticinet

un mab bihan a duy da bout ganet

santel meurbet e bro breton

den leun a gracc dre spacc e prelacj

bara ha dour eguit e saourj

ne vezo muy e hol refection

Euel maz duy dan predication

eno e mam dinan gant estlam don

ne gallo son randon an sarmoner

Palamour rez dan buhez anezaff

a vezo hael pep quentel santelhaff

maz comso scaf ne guallaf rentaf guer

Goude certes courtes ez espreser

buhez ha stat an mab mat hep atfer

pan duy sider e bro bretonery

da pep christen bizuiquen ha tensor

ha cale a joa de ja dre e fauor

ha cals enor da cosquor armory.

Ambrosius Merlinus

I am Merlin, I have foreseen

That a small child will be born

Exceptionally holy in Breton land

Full of grace in the course of his office

Bread and water as nourishment

Nothing more to sustain him

As she will come to the sermon

His innocent mother with great emotion,

The preacher will not be able to speak

Precisely because of his life

Which will be in every way the holiest

He will speak so well I cannot express it

And then indeed will be recounted

The life and state of the good son

When he comes to the Breton country

Forever a treasure to every Christian

And such a joy already by his grace

And much honour for the people of Armorica.

Fragment de Madame de Saint-Prix

A Fragment from Madame de Saint-Prix

Type: Song

Singer: Unknown (probably from Trégor)

Language: Modern Breton

Date: 19th c.

Manuscript: La Villemarqué, Théodore Hersart (1815-1895 ; vicomte de), “Premier carnet de collecte de Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué,” Bibliothèque numérique du Centre de recherche bretonne et celtique (CRBC). Online.

French Edition: Laurent, Donatien. 1989. Aux Sources du Barzaz-Breiz : La mémoire d’un peuple (Douarnenez: ArMen), p. 289.

Madame de Saint-Prix (Emilie-Barbe-Marie Guitton) is one of the pioneers of folklore collection in Brittany. While she never published her findings herself, she acted as a mentor to many younger collectors, not least La Villemarqué. The following poem is often referred to as “Fragment de Madame de Saint-Prix”. While uncertain, Laurent (1989) states that there is a good chance this was collected by her and sent to La Villemarqué to help his research on popular Breton traditions around Merlin. It was mentioned by him in his Barzaz Breiz (1839) as having sent him on the tracks of Merlin in his own area. The original was found by Donatien Laurent in the first fieldwork notebook of La Villemarqué, and he commented on it in his 1989 work on the subject (p. 289-90). The piece appears to belong to the Tale of Merlin type, and has clear parallels with Merlin-Barde. It is this original that is transcribed here.The fragment is hastily written and the narrative is at times difficult to follow due to its fragmentary nature, especially in translation. In particular, episodes appear to be missing, such as the race. I have stayed faithful to the original, but provide some clarifications below, from the other known versions of the story.

Transcript (Laurent’s reading) & translation (FBG)

Merlin Merlin pelac’h etu, hio ! hio ! – aman han. En devez el evoa bet da chasseet, eur loenanic enoua tapet. Pa voa tapet, tapet evoa,

lacet e groë da lardet. Breman e vo tenet en den emez deus e groë; Voeda evo glascet eur higer da e lahet. Pehoa ed da glasque eur hicher da lahet, goulez digan an ani gos a gué vige ed dober tan dindan an dour, et pevoa ed dober tan dindan an dour emen a voa ed quid. Ti an ini goz evoa ed goulen logo – Mi so aouache evit ho logo, bouët da roy dach ne meus quet, me emeuz pem queneg deuz me argant et pempe guennecguet bara en neveus prenet ha ho daou he deveus coainnet. mam gos mar caret ma credet, ebars en allé eus un galompadec. mam gos roit din ho eubel me a ia ivez dar galompadec. ray a ra den hy heubel dont dar galompadec. lacquet he voua den ouarnou plouse. eur garlheden plouse hac eur bride plouse. breman hema ha ya gant he varch da dal an allée hac e voua laret an ini a nige lampet dreiste ar barrier bras ha nigé bet merche ar roué. breman he heont tout an eille vouar lerche éguilée da gavet ar roué, ar roué a goulet digant he verche : hémé hé ! hémé hé ! ac é voua losquet eur banach goat dean gant ar sabren. ar roue a lavaras dean mar a nigé quet digasset violence merlin vras dean, he nigé laghet a nezan. neuse ha ia da galsque ar violans a ve satgeut gant pider chaden aour heuse de vélé, hac en hac he trocho diou anzéz

hac e honnet dar bot sco ac he laret : cant, hac en trocho an diou alle ha he honnet en dro dar bot sco ac he lavaret : cant, hac hen é vonet da gavet ar roué. ar roué a lavaras dezan mar ne nigé quet gallet digas Merlin vras da gavet an nezan en nige lazet an nezan. ac hen ac he tapout ar charraban da vonet da gavet ha nezan. hac e lavaret dezan ha na névoùa quet gouelet un den he passeal enan ha merche ar roué gantan – Leou, émezan, me meus gouelet un den he tremen aman a merch ar roué gantan, ha ma violance a zo eat gantan. hac eman hac he lavaret dezan : - deus geneme ebars ma charaban ac he éfompe hon daou da glasque a nezan. hac hen ac en bacquet an nezan ebars en eur cachet houarne ac alchouhey ar nezan var néan, hac e vonet dar borsse ar roué ac he tisqueè an nezan dean ha pa voua guelet an nezan he voua losquet quite.

Merlin, Merlin, where are you going, hio! hio! – here here. One day that he had gone hunting, he had caught a wren. When it was caught, it was caught, it was put to fatten. Now the man will be taken from his cage; then a butcher will be found to kill him. When he had gone to find a butcher to kill him, he asked the old lady whether she would put water to boil, and when she had put fire under the water he left. He went to an old lady’s house and asked for shelter – I am willing to give you hospitality, I have no food to give you I have five pennies from my money and he bought bread for five pennies and they both dined. Grandma, if you would believe me, there is a horse race in the alley. Grandma, give me your foal, I will also go to the horse race. She gave him her foal to go to the horse race. They put horseshoes of straw on it, and a straw garland and a straw bridle. Now he goes with his horse towards the alley, and he was told that the one who would jump above the great fence would receive the king’s daughter. Now they all went one after the other to find the king. The king asked his daughter: It’s him! It’s him! and a drop of blood was drawn from him with a sabre. The king told him that if he wouldn’t bring him the fiddle of Merlin the Great, he would kill him. Then he went to get the fiddle that was hanging from four golden chains above his bed, and he cut two of them, and he went to a grove of elder trees and he said: A hundred, and he cut the other two and he went again to the elder trees and said: A hundred, and he went to find the king. The king told him that if he would not bring Merlin the Great to him, he would kill him. And he took a cart to go fetch him. And he asked him whether he had not seen somebody passing by with the king’s daughter. -Yes, he said, I have seen a man passing here and the king’s daughter was with him, and he took my fiddle. And he said to him: -Come with me in my cart and we will both go get it. And he caught him in an iron cage and locked him in, and he went to the king’s palace to show him and when he was seen, he was let go.

Clarification: The first part appears to connected to another traditional song, Marv al Laouenan (The Death of the Wren), which Christian Souchon argues is a popular evolution of the Merlin original. This seems confirmed by the capture of Merlin as a bird in Georgic and Merlin (see dedicated page on this website). Then, the competition for the princess’s hand corresponds to the longer Merlin lay collected by La Villemarqué. The unclear dialogue at the end can be rendered as follows, in line with the episode of Merlin’s capture in other parts of the tradition:

The king told the boy that if he would not bring Merlin the Great to him, he would kill him. And the boy took a cart to go fetch him. And [upon meeting a man on the road] the boy asked him whether he had not seen somebody passing by with the king’s daughter. “Yes,” the man said, “I have seen a man passing here and the king’s daughter was with him, and he took my fiddle.” And the boy said to him: “Come with me in my cart and we will both go get it [the fiddle].” And he caught Merlin in an iron cage and locked him in, and he went to the king’s palace to show him and when Merlin was seen, he was let go.

Gwerz Skolvan

The Lay of Skolvan

Type: Gwerz (lay)

Singers: Many from various parts of Brittany, see Laurent (1971) for a more complete list of versions

Language: Breton

Date: 19th & 20th c.

Gwerz Skolvan (The Lay of Skolvan) is known throughout Lower Brittany with many variations. They all describe how Skolvan (or Skolan), who has committed many atrocities in his life, seeks forgiveness on his way to the afterlife. He is forgiven by all but his mother, who describes the many crimes he has committed: Assaulted and killed his sisters (and/or their children), burnt churches, killed a priest, and (most importantly to her) lost her little book, which was written with the blood of Jesus Christ himself. Skolvan restores the book, which had been submerged, and she forgives him, allowing him access to Heaven.This lay not only bears clear parallels with other Celtic traditions (notably the Gaelic Suibhne Geilt and the Welsh Myrddin), but a version of it is found in the Black Book of Carmarthen (Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin, 13th c.) under the title Ysgolan. Donatien Laurent (1971) produced an in-depth study of the known versions, tying it to the broader Merlin tradition. Below is one 20th c. popular version with a translation.

Transcript (as sung by Marie-Josèphe Bertrand, 1886-1970) & translation

Skolvan, Skolvan, Eskob Leon

Zo deut da greiz ul lann da chom,

Zo deut da chom da greiz ul lann

En kichen Forest Kaniskan. (x2)Pan a mamm Skolvan da welet he farkoù,

Kavas an tan war ar c’harzoù (x2)

“Ma bennozh ha hini Doue

Piv en deus ho laket aze

Med ha ma mab Skolvan a vehe !”Pan a mamm Skolvan da welet dour

Kavas ur feunteun toull he dor (x2)

“Ma bennozh ha hini Doue

D'an neb en deus ho laket aze

Med ha ma mab Skolvan a vehe !”Pan a mamm Skolvan da gousket

Terrupl-holl veze okupet (x2)

“Piv zo aze, piv deu aze,

Ken diwezhat-se war vale

Med ha ma mab Skolvan a vehe ?”“Tavit, ma mamm, na ouelit ket,

Ho mab Skolvan zo deut d'ho kwelet.” (x2)

“Mag eo ma mab Skolvan zo aze,

Ma mallozh dezhañ dont alese !” (x2)Oe ket ar ger peurachu c’hoazh

E dad paeron a renkontras. (x2)

“Ma filhor paour, din a lâret,

Deus a-venn oc’h deut, a-menn oc’h aet ?” (x2)“Deus ar pekatoar donet a ran

Sa dan ifern monet a ran.” (x2)

“Ma filhor paour, deut war ho kiz,

Ha me c'houlenney ’vidoc’h eskuiz.” (x2).“Ya, seizh bloaz zo on war an heñchoù

O tresañ ma gwall basajoù. (x2)

O ya, tout holl am eus aedet

Med hini ma mamm n'am eus ket.” (x2)“Ma filhor paour, deut war ho kiz,

Ha me c'houlenney ’vidoc’h eskuiz. (x2).

Ma c’homer baour, kriat oc’h c’hwi

Pan na bardonit ket d'ho kroadur !” (x2)“Penaos Doue m’hen pardonin

D'ar maleurioù en deus graet din ? (x2)

Lazho teir demeus e c’hoarezed

Ha lâret oant inosanted,

Oe ket c’hoazh oe e vrasañ pec’hed !Seizh iliz parrez ‘neus entanet,

Hag ur bern traoù en deus poazhet,

Oe ket c’hoazh oe e vrasañ pec’hed !Mont en iliz ha torr’ holl ar gwer,

Lazho ar beleg deus an aoter,

Oe ket c’hoazh oe e vrasañ pec’hed !Ma levr bihan en doe kollet,

Ya, skrivet gant gwad hom Salver,

Hennezh oe e vrasañ pec’hed !”“Tavit, ma mamm, na ouelit ket,

Ho levr bihan n'eo ket kollet (x2)

‘Mañ er mor don tregont gourhed (x2)

En beg ur pesk bihan o viret. (x2)Tavit, ma mamm, na ouelit ket,

‘Mañ war an daol ront hag eñ rentet,

Faot ket 'barzh med teir feuilhenn c’hlebet.

Unan gant dour, un all gant gwad,

Un all gant deroù ho tivlagad.” (x2)

“Ma bennozh a ran d’am mab Skolvan

Pan eo kavet ma levr bihan !” (x2)Pa gan ar c’hog d’an hanternoz

Kan an aeled er baradoz. (x2)

Pa gan ar c’hog da c’houloù deiz

Kan an aeled dirak Doue

Ha Sant Skolvan a ra ivez.

Skolvan, Skolvan, Bishop of Leon

Has come in a middle of a moor to live,

Has come to live in the middle of a moor

Near Kaniskan Forest.When Skolvan’s mother went to her fields,

She found fire on the hedges

“My blessing and God’s

To the one who put you there

Except if it is my son Skolvan!”When Skolvan’s mother went to get water,

She found a fountain by her door

“My blessing and God’s

To the one who put you there

Except if it is my son Skolvan!”When Skolvan’s mother went to sleep

She was terribly concerned

“Who is there, who comes there,

Walking so late

Would it be my son Skolvan?”“Quiet, mother, do not cry,

Your son Skolvan has come to see you.”

“If it is my son Skolvan there,

I curse him for coming hither!”Her word had barely been spoken

That he met his godfather.

“My poor godchild, tell me,

Whence did you come, whither did you go?”“From Purgatory I come

And to Hell I go.”

“My poor godchild, come back,

And I shall ask forgiveness for you.”“Yes, I have been on the roads for seven years

Fixing all my fell deeds.

O yes, I have helped everybody

But I have not helped my mother.”“My poor godchild, come back,

And I shall ask forgiveness for you.

My poor woman, you are cruel

If you do not forgive your child!”“How could I forgive him

The evil things he has done to me?

Killed three of his sisters

And said they were innocent,

This was not his worst sin!He set seven parish churches on fire

And burnt a lot of other things,

This was not his worst sin!He went to church and broke all the glass,

He killed the priest on the altar,

This was not his worst sin!He lost my small book,

Yes, written with the blood of our Saviour,

This was his worst sin!”“Quiet, mother, do not cry,

Your small book is not lost

It is in the deep sea, thirty fathoms,

Kept in the mouth of a small fish.Quiet, mother, do not cry,

It is on the round table, given back,

Only three wet pages are missing.

One with water, another with blood,

Another with the tears of your eyes.”

“I give my blessing to my son Skolvan

As my little book is found!”When the rooster sings at midnight

Angels sing in heaven.

When the rooster sings at dawn

Angels sing before God

And Saint Skolvan does too.

Further reading:

• Laurent, Donatien. 1971. “La gwerz de Skolan et la légende de Merlin” in Ethnologie française, Tome 1, No. 3/4, pp. 19-54.

La Princesse Yvonne

Princess Yvonne

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Julien Niobé (Canné, Paimpont region)

Language: French (likely from a gallo original)

Name of Merlin: Merlin

French Edition: Orain, Adolphe. 1904. Contes du pays Gallo (Rennes : Honoré Champion), pp. 135-156. Online.

This tale was collected by Adolphe Orain in Higher Brittany and was narrated to him by Julien Niobé of Canné, near the forest of Paimpont (Brocéliande). Here, Merlin’s appearance is only anecdotal.In this tale, a young princess called Yvonne is lost at sea and adopted by two giants who want to marry her to their son when she becomes of age. A prince, who was betrothed to her from birth, travels the world searching for her. When he finally finds the island she is kept on, they plan their escape. The latter is done according to a common motif in Breton folklore: Pursued by the giant, Yvonne transforms herself and the prince into various things in order to cheat the giant. In the end, she changes the prince into an orange tree and herself into a bee. Unfortunately, while it leads their pursuer to give up the chase, they both end up trapped in that shape due to the loss of her magic wand. Merlin appears at the end of the tale, recounted below.Merlin was known in the local area and appears in other tales, including the Tale of Merlin. It is not unlikely that he invited himself into the tale of Princess Yvonne as he was a famous wizard with positive associations whose powers could solve the situation.

Original text

Le roi de Plélan aimait passionnément la chasse, et s’en allait souvent poursuivre les sangliers dans la forêt de Brocéliande. Connaissant parfaitement le pays et les essences d’arbres qu’on y rencontre, il fut un jour bien surpris de trouver un oranger chargé de dix oranges. Il en cueillit une, et son étonnement devint de la stupeur en voyant la branche saigner, à l’endroit où le fruit venait d’être détaché.

Le roi se souvint que l’enchanteur Merlin habitait la forêt, et il l’envoya quérir aussitôt, pour avoir l’explication de ce prodige si nouveau pour lui. Lorsque Merlin arriva Sa Majesté lui dit :

— Toi qui sais tout, peux-tu éclaircir cet étrange phénomène ?

— Parfaitement, Sire. Cet oranger cache un être vivant, métamorphosé par une fée ou un magicien. Les neuf oranges, qui restent à cette arbre représentent les doigts de l’infortuné qui est devant vous et qui nous entend. Le dixième doigt était le fruit que vous avez cueilli, et c’est pour cela que le sang coule.

— Peux-tu rendre à ce malheureux sa forme première ?

— Oui, répondit le magicien, car ma baguette est plus puissante que celle de la fée qui a opéré ce changement.

L’enchanteur toucha l’oranger, le jeune prince apparut aux yeux de tous et alla se jeter dans les bras du roi. Qu’on juge de la joie de ce dernier en embrassant son cher neveu, dont il n’avait plus entendu parler depuis son départ. Lorsque leurs premiers transports furent un peu calmés, le roi fit au prince toutes sortes de questions pour connaître par quelle suite de circonstances, il le retrouvait sous l’écorce d’un oranger.

Le jeune homme lui répondit :

— Mon oncle, je vous ferai plus tard le récit détaillé de mon voyage ; mais, pour le moment, permettez que je m’occupe de ma cousine, que j’ai eu le bonheur de retrouver et qui, elle, se trouve changée en abeille. Tenez, la voyez-vous qui voltige autour de votre tête en nous écoutant ?

Le magicien rendit le même service à la jeune fille. Son père, en la voyant si belle, si charmante, était fou de bonheur, et ne se lassait pas de la contempler. Comme on le pense bien, la chasse en resta là. On retourna promptement au Gué de Plélan, où le mariage des deux jeunes gens ne tarda pas à être célébré.

Le roi céda sa couronne à son neveu qui, pendant de longues années, fit le bonheur de son peuple.

Translation

The King of Plélan [i.e. Yvonne’s father] loved hunting with a passion, and often went after wild boars in the Brocéliande forest. He knew the land perfectly and all the species of trees found there, and he was surprised one day to find an orange tree bearing ten oranges. He picked on, and his surprised turned into awe when he saw the branch bleeding where the fruit had been.

The king remembered that the enchanter Merlin lived in the woods, and he sent for him at once in order for him to explain this phenomenen so new to him. When Merlin arrived, His Majesty told him:

-You who know everything, can you shed a light on this strange phenomenon?

-Indeed I can, Sire. This orange tree hides a living being, shapeshifted by a fairy or a wizard. The nine oranges that are left on the tree are the fingers of the poor soul in front of you, who can hear you. The tenth finger is the fruit that you picked, and that is why blood is flowing.

-Can you turn this unfortunate person back to their original shape?

-Yes, answerd the wizard, because my wand is more powerful than the one of the fairy who operated this metamorphosis.

The enchanter touched the orange tree, and the young prince appeared for everyone to see and embrassed the king. One can guess how happy the latter was to hug his nephew, of whom he had had no news since he left. When their emotion has quieted, the king asked the prince many questions to know the circumstances that had led him to be changed into an orange tree.

The young man answered him:

-Uncle, I will tell you of my travel in details later; but for now, allow me to take care of my cousin, whom I had the joy to find, and who was changed into a bee. Here, can you see her flying around your head, listening to us?

The wizard did for the young lady as he had for the boy. Her father, seeing her so beautiful, so charming, was full of joy, and would not stop looking at her. As you may think, the hunt stopped there. They quickly went back to the Ford of Plélan, where the wedding of the two young people was celebrated without delay.

The king gave his crown to his nephew who, for many long years, made his people happy.

La Fée aux Trois Dents

The Faery of the Three Teeth

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Niobé family, perhaps Julien Niobé (Canné, Paimpont region)

Language: French (likely from a gallo original)

Name of Merlin: Merlin

French Edition: Orain, Adolphe. 1901. "Les contes de l’antique forêt de Brocéliande" in Revue de Bretagne, de Vendée et d’Anjou, Vol. 26, pp. 180-186. Online.

This tale was collected by Adolphe Orain in Canée (Paimpont) from the Niobé family, who provided him with many tales in that region of Higher Brittany.

Merlin is the main character of this tale, that does not correspond to any other narrative type in which the sorcerer appears, at least in Brittany. He is presented here as a young man who gets wealth and success from a magical talisman, rather than a character imbued with magic powers. He also does not correspond to the figure of the Wild Man. It is therefore possible that the association between Merlin and this narrative is a later development due to the relative fame of the character in that part of western Brittany.

Summary

At the beginning of this tale, a couple of wood cutters welcome an old woman in their home during a cold winter night. The old woman reveals herself to be the Queen of Fairies, and to thank them for their kindness she gives their newborn baby a nut containing three teeth from her mother. Each has the ability to grant the child a wish. Once used, the child will need to keep them to avoid the ill-will of evil fairies.

The child, named Merlin, grows to be clever and well-liked, and upon his twentieth birthday his mother reveals to him the power of the teeth. This prompts the young man to leave and see the world, hoping to gain wealth and fame from his talisman.

On his way, Merlin finds an old castle in which he decides to spend the night despite being warned that it is haunted. After having fallen asleep in the most luxurious room in the castle, he is awaken by the ghosts of two knights coming in to discuss a debt one owes the other. Merlin, using his first wish, banishes them forever. He then discovers them to be the long-dead lords of Ponthus and Comper who had fought over the love of a young lady. Ponthus had taken Comper prisoner, and the latter had been unable to pay the ransom, even in death.

Merlin also learns that lord Ponthus had used magic to deprive the neighbouring land of water. The young man offers the inhabitants to restore their water for a small sum of money, which they accept, and he uses his second wish to make the tree blocking the source disappear.

Continuing ahead, Merlin reaches Vannes, where the king is at war with the Franks. Being about to lose, the monarch is offering his daughter’s hand to the warrior who will chase away the invaders. Merlin offers his services, and touching the third tooth, becomes invisible and goes to the Frankish king’s tent to learn his battle plans. This grants Merlin victory in battle, and he marries the princess, offering her a jewel in which the now powerless teeth are encased.

Later on, the jewel is stolen by thieves and Merlin castle’s burn, the harvest fails, and a disease strikes the land. Merlin remembers the warning of the Fairy Queen and goes to retrieve the teeth. He dresses as a monk and gets captured by the thieves. Once in their lair, he sees the jewel worn by the bandit chief’s daughter. He ingratiates himself to her so that he becomes free to come and go, and one day steals the teeth back. Once back home, he gives the talisman back to his wife and opulence is restored to their land.

The Tale of Merlin

Type: Folktales

Language: Breton & French

Date: 19th & 20th c.

Editions: See individual entries.

The Tale of Merlin is the most extensive corpus concerning this character in Breton popular tradition. At least seven versions were collected, six in Breton-speaking Brittany (Western), and one in Gallo-speaking Brittany (Eastern). Luzel mentions it as being quite popular in many regions of Brittany (see Luzel's Anecdote). To these need to be added two sung versions: The gwerz of Merlin Varz (Merlin Bard) collected by La Villemarqué, as well as the fragment collected by Madame de Saint-Prix.The tale is usually, though not universally, divided in two parts. The first one recounts the capture of the Wild Man (ATU502) by a young woman disguised as a man. In most versions, the girl does so as her father cannot fulfil his military duties towards the King, being too old and without a son. The young girl attracts the Queen’s ire, who attempts to get rid of her. She says to her husband that the girl (whom they believe to be a young knight or page) boasted about being able to capture Merlin, a fit deemed impossible. The girl accepts the challenge and uses her cunning to set a trap, usually attracting her pray with food and drink, and using a bed as a cage. In some versions, she is helped by an old witch or fairy to do the deed. The details of this episode vary, but the overall action remains the same. This corresponds to Robert de Boron’s Grisandole episode in the Merlin-Prose, sometimes extremely closely. Paton (1907) studied this episode but seemed to only have been aware of the Captain Lixur version of the tale, therefore looking at it simply as another version of ATU502 in relation to De Boron rather than comparing the full Breton tradition to the Arthurian romance.The tale then usually goes on to a second part, though not in all versions. In that second part, the King’s son frees Merlin despite his father’s orders. As this would mean him being put to death, he flees the court with the help of the Wild Man, who promises to come to his aid when time comes. The young Prince becomes a servant in a distant court that is threatened by a multi-headed dragon who demands human sacrifices. The Princess is to be next, but the Prince summons Merlin to help him fight off the beast and save her. The young man, taking the appearance of three different knights, fights the dragon for three days. The Princess is saved but does not know the identity of her saviour. He is finally revealed by presenting the tongues of the dragon, or alternatively through a lock of his hair that the Princess cut on the third day. They marry and the Prince is allowed to see his parents again. In some versions, this results in the curse that had made Merlin a beast be lifted.

Collected Versions

Further reading:

• Marquand, Patrice. 2006. "Merlin, de la tradition brittonique médiévale à la littérature orale de Basse-Bretagne" in Session de formation de la Société de Mythologie Française (Landeleau). Online. Accessed July 2025.

• Paton, Lucy Allen. 1907. "The Story of Grisandole: A Study in the Legend of Merlin" in PMLA 22/2, pp. 234-276.

• Philipot, Emmanuel. 1927. "Contes bretons relatifs à la légende de Merlin" in Mélanges bretons et celtiques offerts à M. J. Loth (Rennes, Paris), pp. 349-363.

• Philippe, Jef. 1986. War roudoù Merlin e Breizh (Lannuon: Hor Yezh).

Jozebig ha Merlin

Jozebig and Merlin

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Jean-Louis Rolland (Trabriant, Cornouaille)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Merlin

Breton Edition: Philippe, Jef. 1986. War roudoù Merlin e Breizh (Lannuon: Hor Yezh).

Recordings: • Rolland (le), Jean-Louis (1904-1985), recorded by Donatien Laurent in 1965. Jozébig (in three parts), available on Dastumedia, Fiches Numériques 67620106, 67620201, and 67620301. Part 1 online ; Part 2 online ; Part 3 online.

• Rolland (le), Jean-Louis (1904-1985), recorded by Albert Trévidic in 1957-1967 (uncertain). Jozebig ha Merlin, available on Dastumedia, Fiches Numériques 26527, 26528, 26529, and 26530. Part 1 online ; Part 2 online ; Part 3 online ; Part 4 online.

• Rolland (le), Jean-Louis (1904-1985), recorded by Mikael Madeg on 23/07/1976. Josebig ha Merlin, available on Youtube. Part 1 online, Part 2 to come on Brezhoneg Bew.

Summary

In this version of the tale, a general named Duge retires after having been the most successful officer to the king. War breaks and he is called back to duty, but is now too old to go and has no son to send in his stead, only three daughters. The oldest and second one offer to go for him, disguised as boys, but they quickly come home after having been scared off by brigands. In truth, it was their father disguised to test them. The youngest daughter then goes in turn and does not get scared off, finally reaching the court. The young woman wins every battle she is sent to and attracts the jealousy of others, who trick the King into asking her to capture Merlin, a task deemed impossible. After laying a trap in the forest (using food, drinks, and an iron bed that closes on its own), she brings Merlin to the King. The young girl is revealed and marries the King, giving him a son named Jozébig.

In the second part of the tale, Jozébig is playing with three golden spheres. They each fall into the dungeon were they are kept by Merlin, who refuses to give them back. When the third one falls, Merlin asks the boy the retrieve the key to the cell in exchange for the ball. The boy does it, but as it comes under penalty of death, he is forced to flee with Merlin’s promise to help him when in need. Starving in the woods, Jozébig is given a magic napkin by Merlin that provides food. While eating a feast out of his napkin, he meets three big men who alternatively offer him magical items in exchange for it (a staff that summons four knights, a hammer that creates a silver or a golden house, and a bombard that resuscitates the dead). Jozébig agrees to the trade but every time uses the summoned knights to retrieve the napkin from the sleeping giants, allowing him to keep all of the items. With the help of Merlin he then crosses three kingdoms: The one of geese, ducks, and ants. All three people promise their help when the time comes.

Jozébig finally reaches a kingdom in which he is hired as a shepherd, watching over the royal flock. The Princess falls in love with him and comes everyday to court him, but he ignores her and shows disdain to her affection. While herding, he visits the nearby woods in which three monstruous giants live. He kills them over the course of three days, eventually gaining access to their castle and three sets of magical clothing and horses.

Later, the Princess is to be sacrificed to a terrible, multi-headed dragon. Jozébig, disguised as a knight with his magical clothing and horse, comes to rescue her and the monster asks for postponing the fight to the next day. This repeats twice more, with Jozébig being each time disguised as a different knight. He wins and disappears, keeping the dragon’s severed tongues. The Princess and the King decide to look for their benefactor, and attempts to capture him thrice, but he every time gets away. Eventually he reveals himself by showing the tongues and is promised the Princess.

In the last episode, Jozébig returns home to reunite with his parents, but is emprisoned due to his original crime. Using his magical items, he succeeds in securing his pardon and reveals that Merlin had been bewitched, and is now freed from the spell. He also frees the three animal Kings (goose, duck, ant) who were under the same spell.

Learning Jozebig Ha Merlin

Type: Information about a folktale

Storyteller: Jean-Louis Rolland (Trabriant, Cornouaille)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Merlin

Recording: Rolland (le), Jean-Louis (1904-1985), recorded by Donatien Laurent in 1965. Questions sur la technique de mémorisation des épisodes du conte “Jozébig et Merlin” available on Dastumedia, Fiche Numérique 67620302. Online.

In this recording, Donatien Laurent asks Jean-Louis Rolland about the nature of Merlin (see transcript below), and about his memorisation techniques. Rolland explains the tale was only told to him twice on purpose by the storyteller he learnt it from. Laurent published an article about that exchange in 1981 (see ref. below).

The excerpt below is the very beginning of the recording about the nature of Merlin. He is said to have been a king, a direct ancestor of the King of France, who by the 19th c. had become the default king of Breton stories.

Transcript (Gurvan Lozac'h, Brezhoneg Bew), bennozh dezhañ & translation (FBG)

D. Laurent: Poa ket bet lâret piw oa Merlin ?

JL Rolland: Ah ! Heñ vije ket gwraet 'med Merlin 'naoñ, an tad-kozh !

DL: Med…

JLR: E dad-kozh daoñ, e dad-kozh… Tad-ïou, tad-ïou-kozh roue ar Vrañs oa hezh, pigur lâren dac'h 'n-ur c'hwitelled ba…

DL: Heñ oa Merlin ?

JLR: Heñ ?

DL: Merlin oa tad-ïou-kozh, tad-ïou…

JLR: Ya ! Ar re-he oa toud ! Ar rouaned : roue ar gwaied ! Roue ar gwaied, roue an houïdi ha roue ar merien, ha Merlin, ar re-he oa rouaned toud !

DL: Ah yè ! Yè !

JLR: Toud ! Ar re-he na 'n-ur c'hwitelled ba… Pe ar c'hwitell, ar re-he oa dilivret toud deus didan gasell-gê.

D. Laurent: Didn't you say who Merlin was?

JL Rolland: Ah! He was just named Merlin, the grandfather!

DL: But…

JLR: His grandfather, his grandfather... He was the great-great-grand-father, the great-great-great-grandfather of the king of France, as I was saying he whistled in...

DL: He was Merlin ?

JLR: What?

DL: Merlin was the great-great-great-grandfather, the great-great-grandfather...

JLR: Yes! They all were. The kings: King of the Geese! King of the Geese, King of the Ducks, King of the Ants, and Merlin, they were all kings.

DL: Ah yeah! Yes!

JLR: All of them ! These, through the whistle... The whistle, they all were freed from the curse.

Further reading:

• Laurent, Donatien. 1981. “Les procédés mnémotechniques d'un conteur breton” in Cahiers de Fontenay, 23, pp. 34-42.

Kavalier ar Gergoat

The Knight of Kergoat

Type: Folktale

Storytellers: Louis le Corre (Gourin, Cornouaille) ; Yeun ar Gow (Pleiben, Cornouaille).

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Merlik

Breton Edition: Gow (ar), Yeun. 2013. Marc’heger ar Gergoad (Lannuon: Hor Yezh).

Recording: Corre (le), Louis, recorded by Donatien Laurent in 1968. Kavalier ar Gergoad (in two parts), available on Dastumedia, Fiches Numériques 68400307 and 68400401. Part 1 online ; Part 2 online.

Summary

The following is a summary of the Pleiben version.

This version begins as an elderly noble is called to serve in the war. Failure to do so would mean losing his domain, but he has become too old and has no son left to go in his stead. His three daughters alternatively offer to go disguised as men, but the two oldest quickly get scared off by brigands after having disrespected an old woman asking for some help. Eventually, the youngest daughter goes and is not scared off. She also shows kindness to the same old woman in the woods, who reveals herself to be more than a mere beggar and promises to come help the young woman when need arises. Arrived at the court, the knight is tasked to attend to the Queen Mother, who decides to marry her off to a young lady-in-waiting. The disguised daughter refuses, upsetting the Queen Mother. She is condemned to try and capture Merlik as a punishment, a task deemed impossible. With the help of the old woman she met earlier, she captures Merlik using birds and an iron cage that closes on its own. Merlin is paraded in the street, where he reveals that the knight is in fact a woman, but people do not believe him.

In the following episode, the Queen Mother, still upset, gets the young knight on a mission to India to ask the hand of the local queen for her son, the young King of Brittany. Once again, the diguised daughter asks for the assistance of the old witch, who comes to advise her. On her way to India, she helps the King of the Fish, the King of Geese and Ducks, and the Queen of Ants, who all promise to come to her help when need arises.

Arrived in India, the knight is asked to fulfil some tasks to obtain the Queen’s hand, which is done with the help of geese, ducks, and ants. The Queen of India accepts to go to Brittany then, but once arrived, refuses to marry the King until a golden key that she let fall at the bottom of the sea is found. The young knight obtains the key with the help of the fish, and the wedding is planned.

During the banquet, Merlik, who is now the King’s bard, reveals once more that the young knight is in fact a woman. Seeing it, the Queen of India asks to break the engagement so that the King can marry the young heroin, which is done.

The Nature of Merlik

Type: Information about a folktale

Storyteller: Louis le Corre (Gourin, Cornouaille)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Merlik

Recording: Corre (le), Louis, recorded by Donatien Laurent in 1968. Questions diverses sur le conte "Kavalier ar Gergoad", available on Dastumedia, Fiches Numériques 68400402. Online.

In this short recording (1:35), Donatien Laurent and Louis Le Corre discuss the nature of Merlik, the Merlin avatar of the tale Kavalier ar Gergoat. The storyteller had no knowledge of the background of the character, but clearly states the following at the beginning (my transcript and translation):

Transcript of the original and translation

Donatien Laurent: Piv oa Merlik ? Merlik, daoust hag e oa ul loen peotramant...

Louis Le Corre: Un den.

DL: Un den e oa ?

LC: Un den.

DL: Un den?

LC: Un den, ya.

DL: Un den a oa...?

LC: Ya, Merlik a oa sauvaj, koa.

DL: Ah, sauvaj e oa.

LC: Sauvaj.

DL: A oa o chom e-barzh ar c’hoad ?

LC: Ah ya.

DL: Met perak e oa e-barzh ar c’hoad ? Perak oa deut sauvaj ? Penaos oa deut sauvaj ? Oa ket lâret piv e oa, piv oa Merlik ? Deus a belec’h e teue, petra ‘n doa graet...

LC: Nann nann, ma oa [lâret], me ‘meus ket bet goueet.

Donatien Laurent: Who was Merlik? Merlik, was it a beast or...

Louis Le Corre: A man.

DL: It was a man?

LC: A man.

DL: A man?

LC: A man, yes.

DL: A man who...?

LC: Yes, Merlik was wild.

DL: Ah, he was wild.

LC: Wild.

DL: He was living in the forest?

LC: Well yes.

DL: But why was he living in the forest? Why had he gone wild? How did it happen? Was it not said who Merlik was? Where did he come from, what had he done...

LC: No no, if it was said, I didn't know.

Merc'h Markiz Koatleger

The Daughter of the Marquess of Koatleger

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Unknown (likely from Trégor)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Aerlin

Breton Edition: Uhel (an), Fañch [François-Marie Luzel]. 1988. Kontadennoù ar Bobl 3 (Rennes: Al Liamm), pp. 107-121. Online.

Summary

In this tale, an old aristocrat comes back from the war but is asked to return to fight almost immediately. His three daughters offer to go in his stead, but he scares off the oldest two disguised as a brigand, to test them. His youngest daughter pushes through, not letting herself be scared. In the woods, she meets an old woman whom she helps cross a river. As a reward, the old woman reveals herself to be called Gwrac’h Koz an Inkonu (Old Witch of the Inkonu) and promises to come to her help whenever the need arises. Later on, the young knight meets four incredible people who become her servants: Fañch Kreñv (a man with supernatural strength), Yann Kofek (a man who can blow powerfully from his enormous belly), Youen ar Reder (a man who can run several miles in one step), and Job al Lagadek (a man who can hit a target miles away).

They all arrive in Paris, where the diguised daughter becomes attendant to the Queen. The latter wishes to court the young page, thinking her to be a boy, but is rejected and plans for a revenge. She gets her husband the King to send the daughter to find Caesar with the order to bring back his crown and a tooth from his mouth. The young knight goes to Caesar and with the help of her four comrades obtains his treasures, his crown, and a tooth.

Once she is back, the disguised daughter is once again set up by the Queen, and asked by the King to capture the Aerlin, a horned snake that has been terrorising the country. To help her, the knight calls upon Gwrac’h Koz an Inkonu, and the Aerlin is trapped. The beast then speaks: “It was said to me I would be captured by a girl disguised as a knight.” (Lavaret mat e oa ’vijen kemeret gant eur plac’h yaouank gwisket en marc’heg.).

Once back at the palace, the Aerlin reveals the Queen’s lies and she is executed. The Aerlin also reveals the young knight’s true identity, and she is married to the King.

Le Conte de Merlin

The Tale of Merlin

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Véronique Paris (Talensac, December 1859)

Language: French (likely from a gallo original)

Name of Merlin: Merlin

French Edition: Foulon-Ménard, Joseph. 1878. “La tradition de Merlin dans la forêt de Brocéliande” in Mélanges historiques, littéraires, bibliographiques, Vol. 1 (Nantes: Société des bibliophiles bretons et de l’histoire de Bretagne). Online.

Summary

Two sisters, Jeanne and Marie, dress as boys to find employement at the court. The former becomes a cook and the latter a page. The Queen takes a dislike to Marie and has her sent to the dungeon. She is suspected of being a girl, and a witch is consulted who says that if the young page manages to capture Merlin, then he is in fact a girl. Using birds, food, and an iron cage, Marie manages to trick Merlin and captures him, after what she is revealed along with her sister. Both being liked however, they are kept in their employement and Merlin is locked in the dungeon.

The King’s only son, Pelo, is one day playing with a golden sphere that falls into Merlin’s cell. In exchange for the toy, Merlin asks him to open the gate, which the boy does. The sorcerer promises to help him when the time comes, and Pelo has to run away to avoid execution for having freed Merlin. Marie comes with him at the behest of the Queen, and becomes his foster-mother.

They both reach the kingdom of Barenton, where a seven-headed beast terrorises the land, asking for sacrifices. The young Princess, who has befriended Pelo, is chosen. With the help of Merlin, Pelo fights the dragon for three days, each day coming disguised as a different knight. The King and Princess look for her saviour, and eventually Pelo comes forth by showing the severed tongues of the dragon. Merlin reveals that he was under a spell and is now freed, and marries Marie. Pelo marries the Princess and is forgiven by his father.

Ar Murlu

The Murlu

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Guillaume Garandel (Plouaret, 1871)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Murlu

French Edition: Luzel, François-Marie. 1887. Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne, Tome 2 (Paris: Maisonneuve & Ch. Leclerc), pp. 296-313.

Online.

Summary

An old lord has three daughters who dress as knights to go serve under the King of France. The first two are scared off by their father dressed as a brigand, but the youngest succeeds and reaches the court. The young girl, Aliette, becomes the Queen’s page. The Queen falls in love with her (thinking she is a man), but dies shortly after from sadness due to being rejected. Then, Aliette is wrongly blamed for having made a servant girl pregnant, and is revealed to be a woman. Eventually, the King marries her and they have a son.

Later, a Murlu (an extraordinary creature) is seen in the woods and the King demands that he is captured. The Murlu is captured by soliders using food and an iron cage. The creature tricks the young Prince into freeing him, promising to help him when need arises. To avoid execution, the Prince runs away on the Murlu’s back.

They both arrive in the kingdom of Naples, where the boy becomes a shepherd. The Murlu gives the Prince a magic sword to defeat a giant threatening his flock, and the boy takes ownership of the giant’s castle, which is full of treasures.

One day, as he is in the wood, he meets the local Princess being sent as a sacrifice to a seven-headed monster. The Murlu, transformed into a steed, takes both young people to the dragon’s den, where they fight, the Murlu vomitting water on the monster’s fire. After two days of fighting, the dragon is killed. The Prince refuses to go to the castle with the Princess, and both her and the King look for him. He is eventually revealed and maries the Princess.

During the banquet, the Murlu appears and turns into the first wife of the King of France, who was cursed after falling in love with her page (the Prince’s mother). Now, the curse is lifted, and she is free.

Le Capitaine Lixur

Captain Lixur

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Jacques ar Falc’her (Plouaret, January 1870)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Santirine (br) or Satyre (fr)

French Editions: Luzel, François-Marie. 1887. Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne, Tome 2 (Paris: Maisonneuve & Ch. Leclerc), p. 314-340. Online.

Luzel, François-Marie. 1871. “Cinquième Rapport sur une Mission en Basse Bretagne,” in Archives des Missions Scientifiques et Littéraires, Troisième Série, Vol. I (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale), pp. 18-20.

Summary

An old lord is called to the war. He has three daughters who one after the other offer to dress as knights and go in his stead. The first two are scared off by their father dressed as a brigand, but the youngest succeeds and reaches the court. She is so good with weapons that after a year, she becomes a captain. The Queen asks that the young officer be made her page, and the disguised girl becomes known as Captain Lixur. The Queen falls in love with Lixur, not knowing she is in fact a woman, and her favours create jealousy in the court.

To get rid of the young knight, they have her sent to the forest to hunt a terrible boar that no-one has been able to vanquish. Once in the forest, Lixur helps an old woman who turns out to be a fairy, and who in return tells her how to kill the beast. It is done and the knight comes back victorious.

The Queen, vexed that Lixur still pays no attention to her, has her sent to capture the Unicorn that no-one has been able to defeat. Back in the woods, the knight meets the old fairy again, who once again helps the disguised girl to vanquish her foe, which is done.

The Queen, exasperated, has Lixur sent to capture the Satyre, a terrible monster. On the way, the knight meets once again the fairy, who advises her. Lixur uses milk in copper vessels to lure the beast and capture it. It follows the knight back to the court without a fight.

On their way, they meet a procession going to bury a child and the Satyre laughs. Later, they pass by a gallows on which a criminal is about to be hung, and the Satyre cries. Finally, they travel by the shore, where they see a ship about to be wrecked and the crew praying together, and the Satyre laughs once more. They eventually reach the royal palace, where a great celebration is held.

The Satyre then talks to the young woman, asking her to have the King gather all his troops so it can reveal his truths to all. Once in front of everyone, the creature explains the following: He laughed at the procession because he knew the priest was in fact the real father of the deceased; he then cried because the criminal did not want to repent and was about to be taken to Hell; he laughed at the shipwreck because he saw the angels that were about to take the sailors to heaven for their devotion. Then, the Satyre reveals that the Queen’s two ladies in waiting are in fact men. Finally, the creature reveals that Lixur is in fact a young woman, as only a woman could capture him.

The Queen is executed and Lixur marries the King. As for the Satyre, it becomes the King’s prime minister.

Georgic and Merlin

Type: Folktale

Storyteller: Unknown (perhaps from Morbihan)

Language: Breton

Name of Merlin: Merlin

Date: Early 20th c.

French Edition: Cadic, François. 1922. “Georgic et Merlin” in Contes et Légendes de Bretagne (Paris: Maison du Peuple Breton), pp. 207-220.

English Edition: Delarue, Paul. 1956. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), p. 384.

Summary

A marvellous bird is captured by a lord, who threatens of death whoever frees it. The bird, named Merlin, asks the lord’s son Georgic to free him, in exchange of which it will come when called to help the boy. To avoid death at his father’s hand, the boy runs away with a merchant and becomes a shepherd. When the merchant refuses to pay Georgic, the latter calls upon Merlin who uses his powers to get the money. He then gives the boy a whistle to protect him and his flock from roaming wolves.

Later on, the daughter of Georgic’s master is to be fed to a seven-headed dragon who demands yearly sacrifices. With the help of Merlin, Georgic accompanies the princess with a cloak, horse, and sword, and the dragon refuses to come out of its lair, asking them to come back the next day. Georgic comes back thus the next day and the one after, each time wearing a different cloak, and eventually kills the dragon and cuts off its tongues. Three banquets are held and Georgic appears each time wearing one of the three cloaks but vanishing before he can be identified. On the third day he is recognised and marries the girl.

In a second part of the tale, which echoes other Breton fairytales (but not Merlin-related ones), Georgic’s father-in-law becomes ill. In order to cure him, the boy must retrieve three things: A slice of orange from a distant tree, water from the Fountain of Life, and bread and wine from the Yellow Queen. With the help of a magic wand given by a hermit, Georgic retrieves the items.

Merlin Varz

Merlin the Bard

Type: Gwerz (Lay)

Singer: Unclear, perhaps Annaïk Le Breton, née Huon (Kerigazul, Nizon, Cornouailles), see Laurent (1989: 296)

Language: Breton

Date: 19th c.

Manuscript: La Villemarqué, Théodore Hersart (1815-1895 ; vicomte de), “Premier carnet de collecte de Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué,” Bibliothèque numérique du Centre de recherche bretonne et celtique (CRBC). Online, pp. 303-305 & 295-295.

French Edition: Laurent, Donatien. 1989. Aux Sources du Barzaz-Breiz : La mémoire d’un peuple (Douarnenez: ArMen), p. 238-244.

This gwerz (lay) clearly belongs to the Tale of Merlin tradition. In it, a young lad is tasked by the king to steal from Merlin (also named Melin in the original). With the help of his mother, who has magical abilities, he manages to do so before finally capturing Merlin himself. With the Fragment de Madame de Saint-Prix and Georgic and Merlin, it is the only version of the Tale of Merlin in which the protagonist is male rather than female. However here it is not the protagonist who captures Merlin, but his mother, therefore connecting back to the gender aspects of the tale.The version presented by La Villemarqué in his Barzaz Breiz (1839) was at the heart of the controversy that led many to consider him a fraud, and the gwerz was deemed to have been written by him entirely. Laurent (1989: 287-296) carefully studied the original fieldnotes of La Villemarqué and concluded that while the published version is heavily edited, it is indeed originally from popular tradition. The first part of La Villemarqué’s version is missing from the manuscript, a fact that Laurent associates to missing pages based on material evidence (1989: 287). What is now available starts as the king tasks the hero to steal Merlin’s ring, following the horse race (see Fragment de Madame de Saint-Prix).The text below is only from the manuscript, the missing 82 first lines being available in editions of the Barzaz Breiz and online.

Original text (Laurent’s reading with FBG additional readings) & translation (FBG, with revised punctuation for clarity)

The presence of ??? marks a passage that neither Laurent nor myself could read due to challenging shorthand. The presence of ... reproduces suspension marks left by the collector himself.

Laurent's edition also gives the variations recorded by La Villemarqué from different versions. I have omitted them here, but for more, refer to pp. 240-244 in Laurent, 1989.

Mar gasses din-me he vijou

A zo gant-hen en he zorn dueu,

Mar teus da ober kement zé,

Te pezo va mech martezéMa mam chetu pes deus laret,

Ann otrou roue, gaouier touet,

Ar roue en deus laret din

Monet da glask bijou Melin;

Ar roue en doa é gwir touet

Am befé he vech da friet,

Am befé he ver da vriet

Pan delin vije distaghet,

Ar roue en deus guir touet

Hag en deus he toret

Ar roue en doa eul lé gret,

Ha pedall en deus hen torret.Ma mab bihan na chiffet ket gan kement zé,

Tap eur skoultrik a zo aze;

Tap ar skoultrik zé an derven

A zo enen tregont dellien,

A zo enhen tregont delien,

Ken kaer egh[et] aour melen

Bet onn bet seiz noz d’he glasket

E seiz koat goellet.Kement den a zo kousket dous,

Pa gano [a]r c’hog da anternos,

Da marchik vo dioude c’hortos,

Diouda chotos var toul an nor,

Ho cgortos an nor da zigor;

Da di Melin a vit kasset,

Ga da mar bihan en eur red,

Da di Melin a zo kousket

En he guele heb sonj ebet

Ne peus ket da gahout aoen bet,

Melin vars ne ziuno ket

Kemer a refes he vijou

A zo gant hen en he zorn dueu;Pa zeuas ar c’hog da gana,

Ar vijou oa lamet gant ha,

Antronos, pa darzas an dé,

Oa ouet da gahout ar roué

Autrou roué & ...

...

Ar vech mé...

...

Hag ar roué dal ma welas

Chomas, neur sonj sepantet bras

Hag an holl dut a oa ennan

Chetu gonet he grek gant hen

Hag ar rouanes a zeuas,

Ha {kejas} dre kichen he goaz,

Ar rouanes, mab ar roué,

Hag an den barvet kous ive.

Guir ma mab pez a zo laret

Te a peus ma mech gonezet;

Hoghen eun dra choas a c’holan,

Eman a vo an divezan;

Mar out vit ober kement zé

Te a vo ar gwir mab d’ar roué

Ma out vit ober kement zé,

Te pezo va mech dré va fé,

Te pezo va mech, ag ouspen,

An holl bro gwenet dré va fén.

Digass Melin bars kreis al lés,

Da veuli ar briadélesMelin Melin pleac’h et-hu,

Toulet ho dillad an dou tu ?

Paourkes Melin pelec’h etu,

Saotret ho bragou gant ludu,

Gant ludu, gant pl???aboulen,

Plech etu, ta, dieerien;

Evel eur paourkez dier méz

Hag en ho torn eus vas kelen,Pelech {en eon} ta evelhen;

Keler en tu benak va delen;

Klasket tu bennak ma delen,

Ha dallé he poez argant guen

Ha dallé he poes argant guen

He poues en argant hag ouspen

Klas va delen paour evelhen

A oa ma confort er bet men,Melin, Melin, ne welet ket,

Ho telen ne ket kollet

Na kenbet ho bijou ru

Eur pellezenik, d’an dou tu;

Melin, Melin, distroet andro,

Kemer {er gwelé} but a zoKlas ma delen ha ma bijaou

Pere emeus kollet ho daouMelin deut tré bars an ti ni

Da zibri eun tam ghenomp ni,Kement oa bet pedet gant hi

A zeuas Melin bars an ti.

Keit a oa Melin o tibi boet,

Potr rafellik a oa digouet;

Rafellik a oa bet souezet

Né ouié daré plech terret

Raffelik a oa souzet

O guelt Merlin tal an oallet

Ouié daré plech terhetBoemet oa bet gant tri avalik ru

O guelet Melin tal an oalet

Hag he fen gant hen

Hag he benn stouéét,

Hag he benn gant hen stoueet

Hag oc’h he klevout diroc’het

Ar potrik ao souzetTavet ma mab, na rit ket trous,

Kouet eo en eur chousk dous,

Kouet e ganin en eun hun dous

Ha breman ma dal {ganin me}

Te vezo vi guir mab dar roué,Mevel ar pales lavaré

Dar rouanes ar mintin zé

Ar rouanes a lavaré

D’he plach a gamb an de zé,

Petra choari gant dut er gher,

Pé zo kement trous e gheper;

Gant kereno a ran an nor porz

Gant an dud eno ioual forz

Neus netra neve erruet

Nemet Merlin a zo digwet;

Ha daou pen kesek zo gant he,

o sacha he c’harik aman,

ha daou pen kesek, sternet flam

unan zo du an all zo kan;

unan zo dar pot en deus gonet

ho mechik ui da firiet;

ann ini all a zo d’he vam

eus vaosik kous guisket e kan.Hag ar roue dal ma glevas

Trum euz he guelé a zaillas,

Ha gant ann diri ez eas,

Ha da doul nor porz à lampas.

Iechet mat deoc’h otraou roue;

Chetu me deuet adarré;

Iehet...

Me a mo ho mech ar wech mé.

Chansvat a heul chans awalen

Chans d?? chans vat bepret;

Chansvat ha heul chans [awalen]

Evel {chans} neve chans ???,

Vel delliou{,} delliou sechet,

Vel bilim ru, spern du flastret,

Kementra deus he lezen gret

Chansvat...

...

An ??? heli an goanw

Hag an goan da heul an ???Da gahout ar cheler a zeuas :

Sav al leze keler mat,

Ha kerz {o} vale bro timat,

Ha kerz da laret tro var dro,

Penos eur fest ben tri dé vo;

Ha laret dan hol dut ar vro,

Dont dan euret neb a garo.

Dutchentilet ha vochisien;

Ha flech ivé ha kontet ken;

Kontet ive ha vochisien;

Ha tud divar mes ha paorien;

Ha pourien ha tud pinvidik

Na fallo na vara na kik,

Na kik na dour vel da eva,

Na skabellou da azea

Ha kant mevel d’ho servicha.

Triwech pen morgoues vo laet

Ha trivech oen vit ann euret;

18 inar, trivech garo,

Dan enor na mab an otro,

18 inar, nao zu, nao wen,

Vo reit ho chogen da bep eun

Laret dan holl bras ha bihan;

Hep dale bet da ghemen man’r chemengader pan deus klevet,

Da ober he zro eman oet

Dal ma glevas,

Da ober he zro ez eas

Chilaouet holl ha chelaouet

Karkaniou aour a zo anterkant,

Evit rei dar vaherien goant;

But a zo kant zae gloan vuen,

Evit rei dar veleien;

Evit rei dan tut a iliz,

Hag he, dantelleset bed ar pen;

Karkaniou aour anter kant,

Evit rei da vacherien gan,

Ha minteli glas, leun eur gambr,

Da rei dar choazet da fragal,

Ha pem kant bragou neve gret

Da rei dar re paour da gwisket

Ha kement a jak lien wen,

Ha peghement mui a chupen,

Kik ha souben ha bara guen,

Ha peghement traou all ouspenChemengader dal ba glevas,

D’a ober ehe zro ez eas

Chelaouet holl ho chelaouet

Pez a zo bet gouchemenet :

Chelaouet holl, fleh ha contet,

Pez a zo bet gourchemenet :

An euret a vo ben diriao,

Neb en defo choant a zeuo,

Kik avach a vo da lenia,

Ha dour vel ive da eva,

Ha skabellou da azea

18...

Stall avalch a vezo enan,

Vel neus bet biskoas er bet man,

Deuet holl di bihan ha braz,

Da lakat an alfe n’ho lech

??? ha gour

Da lak an alfe toul an nourPemzekté benak doa badet

Ar festou demeus en euret

Dar mec’her a pe oan digoet,

Kaer vije neuzé da welet;

Endro da gheper hed a hed,

An tier leun a dudjentillet

An tier, ha tud karghet,

Hag ar marchosiou a ronset,

Hag oll tiri o krenon,

Gant an oll dut o tont trenhan;

Gwelet ruiou ??? a aour melen,

Ha lukerna an argant guen;

War an dillat ar vacherien;

Ha minteli gloan ru ha glaz

Ha ganthe bep eul leze noaz;

Lod ganthe karniou n’ho c’houg

Hag holl harnesou war ho choug

Karkaniou aouret pen da ben

’vel ma gleet da vacherien

Kement trous ganthe kreis ar gher

Kement grené an holl tier,

Kement grene an holl tier

Hag ann daou mene tré KemperChilaouet, keginour me ho ped,

Hag ann euret so achuet;

An euret a zo achuet

Tri devez zo flam tremenet;

Achu ar fest hag an ebat

Ne deus neb ??? da lipat.Et é rafellik da Wenet

Ha meh ar roue kerkent althen,

Hag he vam gous kerkent alten